Essentials & Advice

Africa and Middle East

Published on May 3, 2018

In Botswana, the Ultimate Safari Experience

By Michele Harvey

Making your way to the enigmatic landscapes of Botswana in search of a deeper connection to the continent from which all humans came, something timeless awakens inside you. On safari, as your rhythms begin to adapt to the wildlife and nature that surrounds you once more, rising before first light to walk the land and to see animals in their natural habitat, you will be forever changed. From a (very brief) history of Botswana and the San people, to one of the most spectacular bush camps you’ll ever visit, let’s begin…

A Brief History of Botswana and the San People

Because there is precious little documentation, the story of Botswana’s early peoples and patterns of settlement is a complex and rather confusing narrative. However, the San people (Bushmen) are believed to have inhabited Botswana for at least 30,000 years. Long before the arrival of either the Bantu-speaking migrants from the north or European settlers from across the seas, small bands of these mobile hunter-gatherers roamed the great sunlit spaces in search of sustenance and solitude. They comprise a unique culture that, at its peak, spread throughout the vast area from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean, and from East Africa down to the southern coast.

The San culture is one that believes strongly in the ideal of sharing, in the importance of co-operation within the family, between human groups, and with the environment. Custom and conviction exclude personal hostility; nature, both animate and inanimate is sanctified, hallowed in the timeless ritual of the hunt, in dance, and in the lively rock paintings and engravings that grace some thousands of sites throughout the subcontinent.

The Ultimate Stay in Botswana: Jack’s Camp

There is absolutely nothing that can prepare you for one of the most fantastic journeys of all: a visit to Jack’s Camp. You will feel as if you have stepped into 1940s Africa, with its traditional East African safari style, and just ten intimate safari camp lodgings.

There is absolutely nothing that can prepare you for one of the most fantastic journeys of all: a visit to Jack’s Camp. You will feel as if you have stepped into 1940s Africa, with its traditional East African safari style, and just ten intimate safari camp lodgings.

The camp itself was named for one of the legendary pioneers in tourism in this area, Jack Bousfield, who first established Jack’s Camp in the 1960s living here for many years. His son Ralph now manages the camp, which was subsequently refurbished in a traditional East African, 1940s safari style.

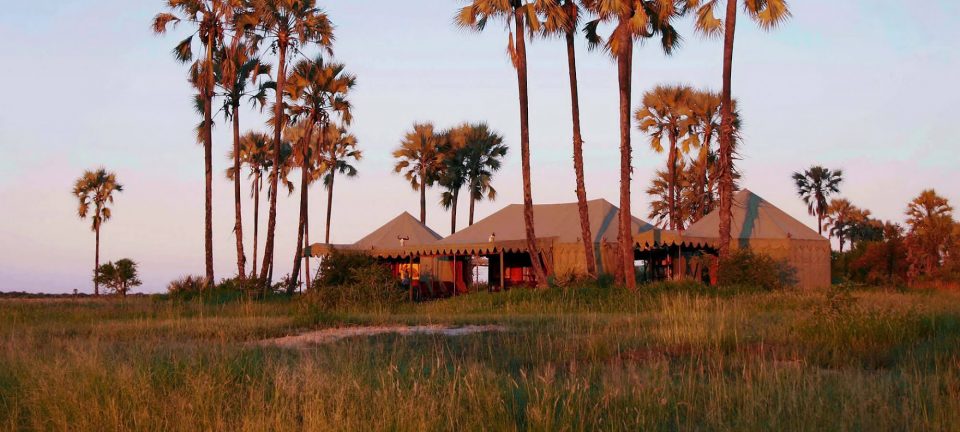

The accommodation, the staff, and the Camp’s informal but rapt attention to life’s finer pleasures make it probably the closest you can get to the authentic British safaris of yesteryear. Accommodation is in roomy, classic tents, with private showers and flush loos, set into an Ilala palm grove. The most incredible combination, The Camp succeeds in creating an elegant oasis of civilization in what can be the harshest of stark environments—the salt pans of the Makgadikgadi and the Kalahari Desert.

Otherworldly Experiences

Many of the guides at Jack’s Camp are qualified zoologists/geologists, many of whom are working on Ph.D. research. As such, they are most able to convey all the nuances of the desert and the adaptations of its inhabitants, some of the most interesting features of the environment.

Many of the guides at Jack’s Camp are qualified zoologists/geologists, many of whom are working on Ph.D. research. As such, they are most able to convey all the nuances of the desert and the adaptations of its inhabitants, some of the most interesting features of the environment.

The emphasis here is on a holistic ecological understanding of the Pans and the surrounding Kalahari Desert. Creative, informal, and intellectual, your experience includes a number of unique interpretative and exploratory adventures, anything from visiting the oldest tree in Africa—the iconic Chapman’s Baobab—to an interpretive walk with the San people, riding horseback or by four-wheeled quad bike in the salt pans, or even meeting the playful meerkats (who will jump on your head) at ‘Meerkat Manor’, a famous burrow in the desert.

In the wet season, you might see hundreds of thousands of pink flamingo on the soda lake at Kubu Island—the greatest flock on earth—or, like me, you will never forget the feeling of seeing, hearing, and feeling the rumble of tens of thousands of zebras on the move across the horizon. Perhaps you will even see the rare brown hyena (different from the more common spotted hyena), or the legendary black-maned lions of the Kahalari desert on your visit; with temperatures soaring to as high as 70 Celsius (158 Fahrenheit) during the day and very little brush for cover in midday, this is an astonishing place of survival.

In the words of French chef Jacques Pepin: “This is the proverbial middle of nowhere, nothing but salt and stars, atmosphere and silence, from horizon to horizon. It’s a place that shifts your axis forever.”

Makgadikgadi National Park

Jack’s Camp is situated on the edge of the Makgadikgadi National Park. It is said that both “kalahari” and “makgadikgadi” stem from the same ancient San word for thirst-land. Both share waterless flat rolling grasslands and scrub, but the Makgadikgadi, which has more water in the wet season, has a particularly desert-like ambience.

The area referred to as the Makgadikgadi Pans is composed of two huge salt pans, Ntwetwe and Sowa, and their associated grasslands. Only a tiny section of this vast area—said to be the biggest salt pans in the world—is actually designated a National Park. You probably wouldn’t even know when you’re in the National Park, since the area is not fenced. The actual surface of the pans is a flat layer of bleached sterile silt that develops a glue-like texture when water is added. Unfortunately, it has an insatiable appetite for vehicles during the rainy season.

Desert Dreaming in the Kalahari

More and more people are being drawn to the deeply spiritual feeling that deserts often invoke. It seems to have something to do with a sense of space and self. It has to do with vast horizons, the huge inverted bowl of the sky, the uninterrupted sweep of the simple landscape beneath it—as featureless as a saucer, with you at its centre. Somehow, it is both humbling and centring. You realize how puny you are, and at the same time, that you are all there is. As American poet E.E. Cummings put it, “when skies are hanged and oceans drowned, the single secret will still be [humanity]”.

Humans have been present around these pans from time immemorial. Indications of a bushman village date the earliest occupation back to 500 BCE. There are bushman hunting shelters probably built and used in the 20th century, made of calcrete boulders that contain fossilized antelope bones and embedded Stone Age tools. The shorelines of Makgadikgadi, for it was more than once a vast inland sea, are littered with the archaeological relics of continuous but scattered human presence. Even when the waters finally receded two million years ago and left these shallow depressions of saline clay and silt to catch the sparse summer rain, the rich herds of wildlife—zebra, wildebeest, eland, gemsbok, springbok, hartebeest—would wander across the plains in ceaseless pursuit of water and grazing. Their presence inevitably drew their following of carnivores—lion, cheetah, leopard, wild dog, and hyena—which of course attracted their own following—the early hunters.

During the dry season, today’s diminished herds of game tend to concentrate in the west, in the vicinity of the Boteti River. With the onset of the rains, they usually disperse to the east and the north, to Nxai Pan and beyond. It is not uncommon to see game far out on the pans eating the mineral-rich silt, as if up to their knees in water as the heat shimmers a mirage across the surface of the pans.

During the dry season, today’s diminished herds of game tend to concentrate in the west, in the vicinity of the Boteti River. With the onset of the rains, they usually disperse to the east and the north, to Nxai Pan and beyond. It is not uncommon to see game far out on the pans eating the mineral-rich silt, as if up to their knees in water as the heat shimmers a mirage across the surface of the pans.

The birdlife is a specialist’s dream: white-backed and lappet-faced vultures, bateleur, ostrich, kori bustard, black korhaan and bronze-winged courser, four species of sandgrouse and a startling variety of larks. In the wet season flamingos, pelicans, avocet and a huge range of ducks move into the area. Sowa Pan, near the town of Nata, is a birdwatcher’s paradise when in water.