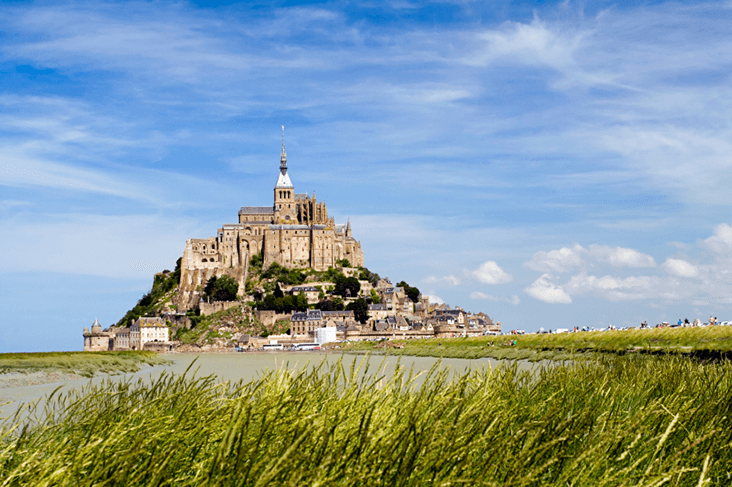

One of France’s most impressive sights, rising almost improbably out of the sea, the spectacular abbey of Mont Saint-Michel is a soaring monument to a divine vision.

It was just a regular day back in the year 708 when, as the legend goes, the Archangel Michael appeared to Bishop Aubert of Avranches (a nearby hilltop town), entreating him to build a church atop the rocky island, then called Mont Tombe. From 966 AD, the dukes of Normandy, followed by French kings, supported the development of a major Benedictine abbey on the rocky mount.

The Higher the Hill, the Closer to God

Built in accordance with the beliefs of the time, the monastery (topped with a gilded statue of Michael) is the highest on the mount, closest to God and the divine. Following beneath is the town, its stores, and the ‘regular’ folk below. While a whopping 2.5 million people visit each year, only about 25 people actually live full-time on the island; the rest return to the mainland.

As for the monks? In 1966 through 1979, Benedictine monks returned for a brief time; since 2001, a community of monks and nuns from the Monastic Fraternities of Jerusalem have also made their home here.

An early pilgrimage site

Mont Saint-Michel has the best seat in the house. Prior to the Reformation, its unique position made it readily accessible at low tide to the many pilgrims venturing to its abbey. (For those in Christendom who could not afford passage to Rome, Spain’s Santiago de Compostela, or to Jerusalem, Mont Saint-Michel was one of the top spots to visit.)

Dangerous quicksand and rapidly-changing tides (which vary by 14 metres or 46 feet) meant that pilgrims had to rush quickly to and from the island. As a result, the exceedingly fluffy, buttery and rich Norman omelets, still served today, were one of the first grab-and-go meals invented out of necessity for pilgrims hurrying to beat the tides.

Dangerous quicksand and rapidly-changing tides (which vary by 14 metres or 46 feet) meant that pilgrims had to rush quickly to and from the island. As a result, the exceedingly fluffy, buttery and rich Norman omelets, still served today, were one of the first grab-and-go meals invented out of necessity for pilgrims hurrying to beat the tides.

(A side note on Norman cuisine: another hyperlocal delicacy you can find only here is agneau de pré-salé—salt meadow lamb. The animals’ unique diet of grazing in salt marshes results in a distinctively flavoured meat—look for it at restaurants in the region).

A permanent causeway was opened in 1879, but today, modern pilgrims have the convenience of a raised bridge, constructed in 2014, to let them come and go at leisure.